Two-Wheeler Makers Don't Want ABS Mandatory Rule: Govt Isn't Relenting

The sound of motorcycles across Indian roads could soon carry more than just speed - it could reflect a brewing fight between safety and survival. From January 1, 2026, the government wants every new two-wheeler in India, no matter its engine size, to be fitted with Anti-lock Braking Systems (ABS). This is a step up from the current rule, which only applies to bikes above 125cc. The goal is clear: improve safety. But manufacturers say they’re running out of time and options.

The problem lies in the numbers. In FY25, India sold over 12.25 million motorcycles, but only 23% of them had ABS. That leaves around 9.43 million smaller bikes that used Combined Braking Systems (CBS) instead. To meet the new rule, ABS production would need to grow more than six times - and fast.

According to a senior executive from a global parts supplier, no manufacturer currently has the capacity to meet such demand. This is not just about money. Building infrastructure, retooling factories, and getting approval for thousands of models - all within six months - is nearly impossible.

Certifying bodies like the Automotive Research Association of India (ARAI) also face a bottleneck. They would need to test and approve a massive number of vehicles in a very short time, which adds to the pressure.

Not everyone agrees that ABS is the only way to improve safety. Rakesh Sharma from Bajaj Auto argues that manufacturers should have the freedom to choose the best way to meet safety standards. He believes that CBS works better for many riders, especially in the entry-level segment, where people mostly use the rear brake.

Experts also point out that ABS works best under certain conditions and with trained riders. In some situations, especially on poor roads or with skilled riders, stopping distances might actually be shorter without ABS.

International data shows that ABS can reduce deadly crashes by 22% to 31%. Still, that does not mean it fits every road or rider in India.

Money is a major concern. Adding ABS could raise the price of a basic motorcycle by ₹4,500 to ₹5,000 - an increase of 4% to 10%. For many people, this could put a new bike out of reach.

The entry-level segment already makes up 75% of the market. But it’s been hit hard by recent cost increases from new emission norms, higher insurance, and fuel prices. Sales still haven’t returned to pre-2019 levels. A further price hike could hurt recovery even more.

Analysts at Nomura think the rule could cut demand by 2% to 4%, meaning the loss of hundreds of thousands of sales and jobs in a sector that directly supports millions.

The government is standing firm. In 2022, two-wheeler deaths rose by 8% to nearly 75,000, accounting for 44% of all road accident deaths. Most of these involved bikes below 125cc. That’s exactly the group the new rule targets.

Many other countries - like those in the EU, UK, Brazil, Japan, Taiwan, and Australia—already require ABS on all motorcycles. Studies in Europe show it cuts injury crashes by 24% to 34%. In Sweden, it reduced fatal accidents by nearly half.

Officials in India believe six months is enough time to make the switch, though they may extend it to eight or ten months if needed.

But unlike Europe, India faces unique problems. Customers are highly price-sensitive, and service infrastructure for advanced electronics like ABS is still growing. For a construction worker or a delivery rider, a ₹5,000 jump in vehicle cost is a big deal.

Then there’s the ripple effect on jobs. Fewer sales mean lower demand for parts, fewer workers on factory floors, and slower business at dealerships and service centres.

ABS and CBS work differently. ABS uses sensors and electronics to prevent wheel lock-up, while CBS connects the front and rear brakes to work together. Both have their strengths, depending on how and where the bike is used.

The good news is that ABS units are getting smaller and cheaper. Bosch now makes a unit that weighs only 0.7 kg and is half the size of earlier models. This makes it easier to install, but doesn’t solve the problem of building enough units in time.

Manufacturers aren’t trying to skip the rule altogether. They’re asking for a more practical rollout. Supply chains for ABS sensors and other parts are already stretched. The recent chip shortage showed how quickly these systems can fall apart.

Bike makers say they need time to build capacity, test bikes, and ensure quality. They also want a fair chance to prove how CBS and ABS work in different Indian road conditions.

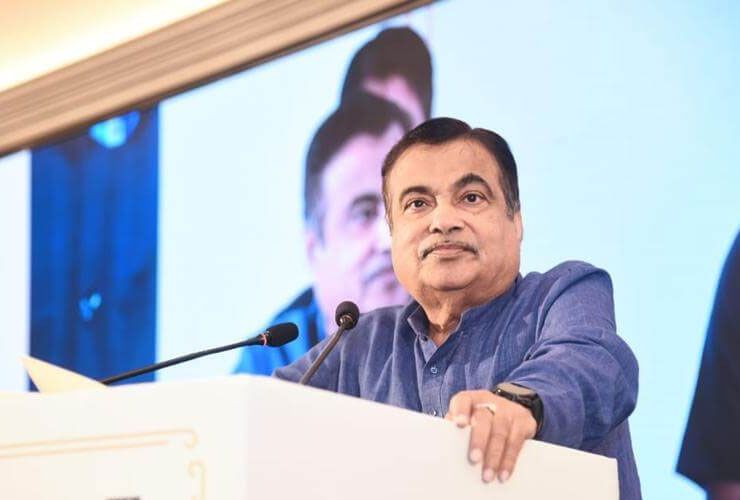

Meanwhile, the government is focused on reducing road deaths. Minister Nitin Gadkari has promised to cut accidents by 50% by 2030, which makes it hard for the ministry to back down from any safety move.

This fight is about more than brakes. It’s about how fast developing countries can make safety changes without hurting people’s access to transport or jobs. It’s also about trust between regulators and industry.

If manufacturers get an extension, it could show that the government listens. If not, it could set the stage for faster safety changes in other areas, like airbags or emission rules.

Either way, what happens in the next few months will shape the future of India’s bike industry. Will it find a way to build better brakes quickly enough? Or will the push for safety come at a cost too high for many to pay? Only time, and a bit of cooperation, will tell.